Chapter two

The Corduroy Neuron

Here is how I think it probably works. The neuron is a multichannel device. Its membrane is functionally analogous to the ribbon cable shown in this photo.

There is no encoding and no decoding. There is no code, no signal processing, and no need to notice and compare the distinct arrival times of a clocking pulse and a sensory pulse.

In a multichannel neuron each spike communicates a number, an integer, which is instantly meaningful upon arrival at the brain.

The model explains why the brain is so fast. It uses numbers.

The brain will read incoming channel numbers as levels — analog increments — not as crisply inscribed Arabic numerals. What we can freely call numbers represent positions in a sequence. In biology, sequence encodes shapes. The genome is a sequence. So the notion of a number line in biology is not as far fetched as it might at first seem.

The model increases the channel capacity of the human nervous system from 1011 up to perhaps 1013 or 1014.

A relatively modest change with striking theoretical consequences.

From the beginning

If the impulse moves slowly, and it certainly does, and we are quick and smart – and yes we are – then each impulse must be freighted with complete information.

To arrive at a fresh model of the neuron, it is necessary to stay within two rules. 1) because it is so slow, the impulse must carry a heavy load of information and 2) whatever the trick, the secret variable, it must elude detection by all the instruments commonly used to study nerves.

Let’s start with the notion that each individual nerve impulse communicates finely graded information that is instantly readable and meaningful to the brain. How to model this?

The corduroy membrane:

Suppose a model axon has 300 discrete longitudinal transmission channels. On the sensory end of this neuron model, a voltage source can be applied to stimulate the neuron in a range between 0 and 300 mV.

In this model, each longitudinal channel corresponds to an increment of stimulus voltage. Channel #1 means 1 mV. Channel #2 means 2 mV. Channel #27 “means” 27 mV, and so on up through Channel #300.

The neuron is now stimulated at some level of intensity, say 35 mV. An all-or-none nerve impulse of the familiar type is triggered and goes chugging down the axon. It looks, to a laboratory instrument, like every other nerve impulse. But it is traveling along a specific longitudinal channel, Channel 35, and in this way it preserves the original meaning of the graded voltage stimulus (i.e., 35 mV) all the way to the end of that channel.

Then what? Probably a separate and distinct synapse for each channel. Perhaps a chemically encoded channel identity, such as a unique peptide, packaged with the neurotransmitter.

There is a semantic difficulty with the model because it depends on the concept of channels — and ion channels are so central to our understanding of the nerve impulse that there is a potential for confusion between the postulated “longitudinal channel” and the ion channels.

In fact, they are the same channels.

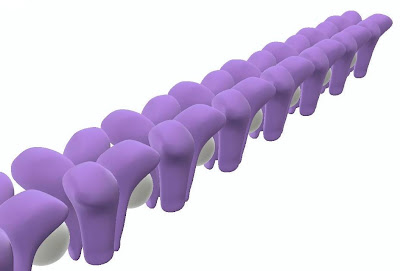

Linked receptors and other linked membrane structures are commonplace in biochemistry. The basic idea is to biochemically link adjacent sodium ion channels in a long line of succession the full length of the axon. This produces one longitudinal transmission channel as long as the axon. Repeat this structure in order to form about 300 longitudinal channels. A corduroy membrane.

In the model, the ion channels are connected with protein links, represented here by white spheres, since they are abstractions. Each single sodium channel (as conventionally understood) is represented in purple by its four homologous transmembrane protein domains.

The only novel element in the model is the conjectural protein link between channels. The link could be in the membrane, under the membrane in the cytosol; it could be cytoskeletal. It is possible that it tugs at the lipid surrounding the vestibule of one or more voltage sensors. But there is no specification necessary in this generalized model, beyond the notion that a link between individual sodium channels exists. Thanks to this link the individual sodium channels have been, in a manner of speaking, polymerized or concatenated to form a long chain.

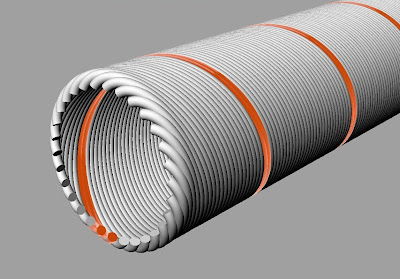

Note that one could wrap these longitudinal channels around the long axis of the neuron, forming a helix embedded in the axon’s cell membrane.

In this helical version of the model, conduction speed would be a function of the period of the helix.

Consequences — at first glance.

The model has the virtue that when a single nerve impulse arrives on channel 27, for example, it is instantly and completely meaningful. It means 27. It need not be counted, clocked, accumulated and averaged or otherwise processed to extract this meaning.

In detail it means, “27 mV were being applied to the sensory end of the nerve at the instant when the impulse was fired down this channel.” In a motor version of the nerve model, the channel number would correspond to a precise positional instruction. Channel 27 means, “bend your elbow 27 degrees.”

The sensory channel number and millivoltage have been made identical here for the purpose of this explanation. A real world Channel #1 would “mean” a voltage level corresponding to the threshold required for the nerve to fire. The neuron could be coarse or fine in resolution, depending on how finely the channels are incremented.

Multichannel neuron membrane. A single channel marked in orange is firing.

Multichannel neuron membrane. A single channel marked in orange is firing.

What’s missing?

A channel selection mechanism. The multichannel nerve model differs from the familiar, conventional one-channel neuron in an important way. A one-channel neuron has only one firing threshold. A multichannel neuron requires a succession of incrementally higher and higher firing thresholds, each corresponding to a channel number. The thresholds could vary linearly but it seems more desirable that they would vary logarithmically.

The channel selector can be modeled as a passive device, simply assuming a staircase of thresholds, but the model becomes more fruitful and intuitive if channel selection is made active, as though by a moving commutator. A shifting commutator model readily reproduces waveforms commonly detected in the lab on real neurons.

Section through the model neuron at the axon hillock, showing one model of a channel selector. This device works like a commutator within its normal range from channel 0 to channel 300. For a given stimulus, it shifts from channel to channel, firing each in rapid succession, until it arrives at a channel where the intensity of the stimulus is matched by the channel number. There it stops.

The channel selector can move in either direction in response to intensity changes. It can also halt, which puts an end to firing. But note that there is no mechanical stop at zero. Because there is no stop, the system is perfectly capable of “motoring” if it is overdriven. This motoring effect could generate and account for Adrian’s firing rate code.

This is a mechanical model of a simple and familiar electrical machine, a commutator. The model does not, however, operate by “making electrical contact” with each channel in turn. Instead it operates chemo-mechanically on each channel terminal, in some sense prising open the initial sodium channel and thus launching an action potential.

The commutator is a metaphor for some real, probably cyclical process that would operate at the molecular level. It is a biochemical machine, and so it is all about binding, conformational changes, and conformational responses to binding. These effects have ultimate consequences we can measure with electronic instruments, like an influx of ions. But the mechanism cannot be fully understood if we insist on regarding it as a purely electrical device. The underlying biochemical twists and shifts and hooks and grabs cannot be detected electrically.

Note that in a mechanical model, the commutator can be made to act as an attenuator by adding a spring that resists the pointer’s rotation. Out of range stimuli could be in effect reined in by a spring whose tension could be varied. This suggests a metaphor for adaptation. It could be that each signal transmitted by the multichannel neuron model has two components, like a logarithm. One number specifies the attenuation needed to achieve adaptation (X5, X10, X50). The second number specifies the position within a reporting range (e.g. a channel number from 0 to 300).

Biochemistry is fast and extremely mechanical, a molecular watch works. The circulating crawler/selector above is reminiscent, in principle, of an enzyme finding and binding its active site, or a ribosome ratcheting along, or a polymerase at work on a loop. Another example at the molecular level is ATP Synthase, which actually uses free rotation, as shown in this animation depicting the work of Nobel Laureate Dr. John E. Walker, Medical Research Council, Dunn Human Nutrition Unit, Cambridge, UK.

In sum, ratcheting, site seeking and recognition, circularized strands, circular strand following and even free rotation are not novelties in nature. One can model a commutator without resorting to mechanisms that feel “unbiological.”

The commutator model can be used to interpret the known firing patterns of neurons, but I will re-emphasize that it is a conjecture, a model. No one has ever looked for such a mechanism.

If you like the corduroy neuron model, therefore, you must simply assume that some sort of threshold sensitive channel-selector and impulse launcher exists on the front end of the nerve, at or ahead of the multichannel axon hillock. This device would point to and trigger off the specific channel that is numerically appropriate to the intensity of an applied stimulus.

A test for the model: reproduce Adrian

Although we are now free to seek alternatives to Adrian’s firing rate code, which was his interpretation of his experimental results — any realistic model must be able to account for and faithfully replicate Adrian’s discovery: Spike frequency must vary as a function of stimulus intensity.

The model does not have to follow this pattern all the time, but it must have in its repertoire the behavior Adrian (and thousands since) observed.

For the multichannel model, if lots of meaningful impulses should happen to travel the axon in rapid succession, it means the stimulus is changing rapidly on the sensory end. In this version of events, the frequency does not indicate the intensity of the stimulus. Rather, it indicates the rate at which the stimulus is changing – rarely faster than in that moment when the stimulus is first applied; or when the stimulus is removed or turned off.

Click to enlarge, Back to return.Notice the two “tufts” of impulses at the onset and offset of stimulus in this oscillogram. In terms of the model, the first tuft indicates that the commutator is winding up rapidly in response to the light stimulus, firing at each increment. The second tuft appears when the commutator winds back down after the light is turned off, firing at each decrement. The illustration is an interpretation of an oscillogram recorded by Hartline in 1938 from a retinal ganglion cell of a frog. It demonstrates one of three patterns he observed and named: “ON,” “ON-OFF,” and “OFF.”

The tufts produced automatically by the multichannel neuron model begin to explain Adrian’s observation, but the hypothesis does not yet account for firing rate variations observed in long pulse streams. To produce this result, it turns out the multichannel model must be overdriven, as discussed below:

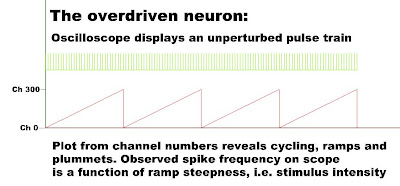

What an oscilloscope cannot show us:

In this multichannel model, what does the detection of a rapid-fire stream of impulses really tell us? In a sensory neuron, it lets us know that the stimulus is changing, and that the last recorded impulse conveyed the most recent value – though we cannot guess that value. A pulse stream could mean 1 2 3 4 5. It could mean 9 8 7 6. It could make an undetectable turn in mid passage, and mean 1 2 3 4 5 4 3 2 1, for a net change of zero.

Speaking of zero, in a multichannel system that has assigned one, a stream of impulses could mean 0, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 0, -1, -2,-3. The system might even break into an oscillatory response that would be completely cryptic — trilling up and down the number line in sawtooth fashion while, to the observer, simply appearing to be firing one spike after another in rapid succession.

For example, a sensory nerve that “fires like a machine gun” could be a nerve that is for the moment overdriven and overwhelmed. This means it is poorly scaled to the size of, and incremental changes in, the received stimulus.

This neuron could run up through its full range of channel numbers, plummet back to zero, and then repeat the cycle again and again.

Click to enlarge, Back to return.

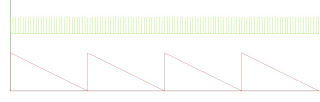

Say 300 is the topmost channel number, and 0 is the next number in a rotation. The commutator increments past 300, seeking a higher channel number, but the next number in turn is zero. The undetected pattern that could be plotted from channel numbers is a sawtooth, but the observed pattern on an oscilloscope screen is just a continuous high frequency pulse stream.

The higher the intensity of the stimulus, the steeper the ramp of each sawtooth and the higher the observed pulse frequency of the continuous pulse stream on the scope. Conversely, the lower the intensity of the stimulus, the gentler the ramp of each sawtooth, and the lower the observed spike frequency, as indicated here:

This hypothetical looping or “motoring” effect fits the model more completely to Adrian’s results. It also suggests that adaptation means scaling, attenuation, zero-positioning. Adaptation stops the motor.

Once adapted, neuron can then operate normally within its range of channel numbers, in this example 0-300. Within this normal operating range, a single spike is sufficient to communicate, as a channel number, the intensity of the stimulus.

Once a multichannel neuron is overdriven and breaks into oscillation, it essentially loses its power to quickly communicate meaningful information with a single impulse. The output becomes a meaningless blur of channel numbers.

The model could be overdriven in either direction. A neuron scaled to a strong stimulus may break into oscillation if the stimulus is suddenly removed.

Notice that the sawteeth are flipped (i.e., with descending ramps) and that the transition or overrun occurs in the 0-to-300 direction, rather than the 300-to-0 direction. The commutator increments toward lower channel numbers, seeking a value that is smaller than 1 or is negative — but it instead finds channel 300. “Motoring” ensues.

Notice that the sawteeth are flipped (i.e., with descending ramps) and that the transition or overrun occurs in the 0-to-300 direction, rather than the 300-to-0 direction. The commutator increments toward lower channel numbers, seeking a value that is smaller than 1 or is negative — but it instead finds channel 300. “Motoring” ensues.

I have included the overdriven neuron hypothesis here in order to emphasize how much busy activity could be happening behind the scenes, and how utterly oblivious an oscilloscope would be to any and all of this activity.

The action potential is a medium, not a message.

However the system behaves and responds, in this multichannel neuron model an action potential is a medium. It carries a message — but it is not the message. The exact message, which is a channel number, cannot be readily deduced from the behavior of the medium.

Experiments (and this implicates all of our experiments) that detect and report the behavior of the nerve impulse as a medium can be perfectly repeatable yet perfectly inscrutable.

If the multichannel model were to prevail, this problem of confounding the medium with the message would raise many questions about the fundamental experiments in neurophysiology. It would also change somewhat the meaning and functions attributed to synapses and neurotransmitters.

The memory neurons

There is a special case: neurons used to sample and store memories.

In the multichannel model, the content of a memory consists of channel numbers, and the atom of memory is a single channel number.

The output channel number of a sensory neuron, a retinal cone cell for example, can change frequently in response to changes in the world. As a first step in making a memory, it is necessary to freeze this stream of changing numbers and extract a fixed value associated with a clocked moment in time. To accomplish this we need a memory neuron that can sample-and-hold the momentary output of a sensory neuron.

Once a sensor’s momentary channel number has been captured and, in effect, time stamped, one could surmise that learning requires the memory neuron to repeatedly fire that specific channel. Repeated firing keeps the captured channel number (5, for example) in play while it is being “memorized”, that is, consolidated along with other numbers simultaneously sampled from other sensors. If the number 5 originated at a single cone cell in the retina, then along with thousands of other simultaneously sampled numbers from other cone cells it could help specify a visual memory, a snapshot image.

The repetition of the number 5 by a memory neuron constitutes a form of short term memory.

A memory neuron can be easily made to fire repeatedly on a sampled numbered channel. If we could read the channel number output, it might be for example 5-5-5-5-5-5, or 131-131-131-131-131. The ability of a multichannel neuron to function as a number repeater is inherent in the model.

One can imagine that the commutator might repeatedly swing through a 360 degree sweep and, upon each rotation, fire an action potential down a single, sampled-and-held numbered channel such as channel 5 or channel 131.

In a sensory neuron we would expect a 360-degree swing to fire all channels, not just one, so there would have to be some technical trick in a memory neuron to single out for firing the sampled channel and no other. This little turn of the hand could in fact be the basis of a sample-and-hold device.

The single-number repeater output could also be achieved in other ways. One is by pinning the commutator arm to a single channel, so that it cannot rotate. Another is by erasing or permanently bypassing every channel that is not part of a memory, leaving only, for example, channel 5.

It could be that a temporarily pinned commutator arm is used to produce and hold a short term memory, and that massive erasure of non-memory channels underlies memory consolidation for the long term — probably in a remote neuron.

Evolution of memory cells

Imagine a very basic memory system in a primitive marine animal. Suppose the animal seeks in the water a gradient of some important nutrient. It then tries to climb that gradient toward a more concentrated source of nutrient. It uses an olfactory sensor to detect the nutrient. The memory exists to hold up for comparison the concentration of nutrient as it was sensed a few seconds ago — with the incoming sensor reading of the concentration of nutrient sensed in the present moment.

In other words, the memory enables the animal to compare the food concentration Just Now with the food concentration Right Now. This tells the animal if it is moving in the right direction, toward the food. The survival value of this little buffer memory is considerable.

You could construct a system like this using an olfactory sensor neuron for the present reading and, as a very short term memory, a repeater type memory neuron to supply the “Just Now” reading. If the animal is moving toward its food, the Right Now reading will be bigger than the Just Now reading. Thus, a simple repeater neuron could have been the kernel of a memory apparatus from a very early stage in memory evolution.

Consolidation

Let’s consider memory storage at the level of a single neuron in an animal that is in the process of learning something. We have suggested that learning requires repeatedly firing a specific channel, in effect keeping a sampled channel number (5, for example) in circulation in a brain network while it is being memorized. This repetition of the number 5 constitutes a form of short term memory.

The process of memory consolidation might be quite destructive. It could consist of eliminating or bypassing or suppressing every channel that is not included in the memory. The idea is elaborated in Chapter 14 in the sidebar, “Memory writing as a destructive process.” Memory recall would then include addressing that particular neuron. That neuron could then reproduce and perhaps repeat for a while the “learned” channel number, in this case 5. The addressing process would necessarily include the rest of the neurons in an “engram” network.

Pixel memory, motor memory, and film strip memory

Finally, note that a repeated firing pattern in an engram neuron need not be restricted to just one monotonous channel number (e.g., 5-5-5-5-5-5). It could easily consist of repeating triplets (2-5-7, 2-5-7, 2-5-7) or quads (2-5-7-9, 2-5-7-9, 2-5-7-9). This would be particularly useful in storing visual (pixel) memories.

If the organism were learning to walk, or to fly, a neuron might be programmed to return a longish series of channel numbers: 3-4-5-6-7-8-7-6-5-6-7-8-3. This number series describes a curve. It could be made to describe a cycle. These would be useful outputs to motor neurons or comparators.

A simple electro-mechanical commutator cannot, without reversing direction, produce a number stream like 3-4-5-4-3. This is not a problem in a sensory neuron, but in a memory repeater, it would be aesthetically neater if the commutator arm rotated in one direction only, like a disk on a spindle. You could accomplish this by adding embellishments and contrivances, but the playback commutator is, after all, just a metaphor. It gives us a way to describe what a basic model of a multichannel neuron can do. A real multichannel neuron would select channels to fire at the molecular level, and biochemistry has complications of its own. So there is not much point turning our simple mechanical commutator into a contraption.

We can see, from here, that a number series memorized and reproduced by a repeater neuron, by whatever means, is a desirable objective.

If we return to the memory read out from a cone cell, a repeated series of numbers, triplets perhaps, can specify a single pixel in a snapshot. With thousands of other neurons simultaneously repeating the specifications of other pixels sampled at the same moment in the past, the snapshot image fills in all at once.

Now, if we concatenate the streams of memory triplets sampled from a single cone cell — sampled at, say, 10 second intervals — we have a produced a memory machine that can walk forward through past time. This is a film strip memory. These ideas about visual memory are elaborated beginning in Chapter 13.

Memory storage, time stamping and addressing

We are pretty close to a descriptive model of a basic memory machine. The first essential component, memory storage, can be supplied by repeater neurons. The mechanism lacks synchronicity, that is, a clock — and an addressing system. The multichannel neuron model can be adapted supply these two missing components. The commutator becomes a clock motor. It can also become the center of a hub-and-spokes network. At the end of each spoke we can mount another hub. This type of addressing system is discussed in more detail in Chapter 14. It can generate and deliver a colossal number of unique address signals.

In general, the multichannel neuron turns out to be a prototype and a parts bin for modeling the brain.

Obviously these conjectures and models are meaningless for a textbook brain that must operate on all or none spikes coursing down one-channel axons. Given the assumption of a multichannel neuron, however, a number of novel memory models become accessible.

The scale of the system

Take a look at Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes, which is the classic book on this subject by Bertil Hille.

One of the surprises in this splendid, fascinating book arises from Hille’s thumbnail history of the very idea of individual ion channels.

It is a much more recent idea than one might suppose. Not until the mid-1960s (well after the Hodgkin Huxley Katz voltage clamp work) did neurophysiologists finally arrive at the now commonplace image of an ion channel as an individual structure – an ion-specific porthole or passageway through the cell membrane.

Hille emphatically characterizes the individual channel as “a discrete entity,” and as “a distinct molecule.” By 1965 this concept had been in the air for a while, but it did not prevail or become the dominant picture until binding studies were conducted with tetrodotoxin and saxitoxin. Largely thanks to this work, by the late 1960s, the author recounts, the names “Na Channel” and “K Channel” began to be used consistently.

The familiar, orderly picture of individual channels embedded in the cell membrane was brought to us by the magic of long division. For example:

“Dividing specific binding by membrane area yields an average saxitoxin receptor density of 110 sites per square micrometer on the axon membranes of the vagus. We now know that the tetrodotoxin-saxitoxin receptor is a single site on the Na+ channel, so this experiment tells us how many Na+ channels there are in the membrane. Surface densities of 100 to 400 channels per square micron are typical …”

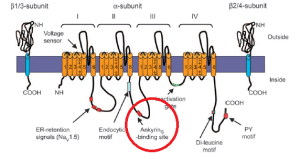

The picture you get is one of barrel like protein ports floating like buoys in the membrane, nicely regimented into rows and columns, anchored at the intersection points of an imaginary grid. It is, of course, an image made ideal by the arithmetic which originally produced it. Here is a diagram of the components of a single mammalian Na channel.

Just beneath the membrane the channels are in fact tethered to the cytoskeleton via Ankyrin, circled in red here. Our understanding of how the Na+ channels are positioned by these tethers is essentially two-dimensional. We know that in myelinated neurons, very dense local concentrations of the channels are maintained at the nodes of Ranvier and at the beginning of the axon. But the positioning of sodium channels in 3-space is not clear. For example, the helical winding of linked sodium channels around the axon is of course a speculation at this point.

Just beneath the membrane the channels are in fact tethered to the cytoskeleton via Ankyrin, circled in red here. Our understanding of how the Na+ channels are positioned by these tethers is essentially two-dimensional. We know that in myelinated neurons, very dense local concentrations of the channels are maintained at the nodes of Ranvier and at the beginning of the axon. But the positioning of sodium channels in 3-space is not clear. For example, the helical winding of linked sodium channels around the axon is of course a speculation at this point.

Hille concludes: “Now that we can record from single channels – and even purify them chemically, and sequence and modify their genes – there remains no question of their molecular individuality.”

Reading this, you get the idea there may have been a rather hot argument, years ago, about the “molecular individuality” of the Na+ channels. Maybe a question was raised about whether tetrodotoxin-saxitoxin receptor was an accurate index to the true number of Na channels. As in fact it turned out to be.

Whatever happened, I think there does remain after all a staggeringly important question about the molecular “individuality” of these ion channels. This is because the channels, though they are indeed distinct molecular entities — can be structurally and functionally linked. Clustered, paired, lined up in rows, bridged.

Linked cell-surface receptors are a commonplace of biochemistry and ion channel linkage is of course the anatomical basis of the multichannel neuron model we are exploring here.

To get a sense of the scale of the model, using Hille’s numbers, visualize a one micron square area of the neuron’s cell membrane, and draw 10 to 20 straight lines across it. The lines represent the passage of 10 to 20 longitudinal transmission channels — each longitudinal channel assembled as a row of 10 or 20 linked Na Channels.

This image shows us the working scale of the hypothetical corduroy membrane surface of a multichannel neuron. I doubt the dimensions are true to life – too neat.

The channels could be packed thick or thin, and they could run helically around the long axis of the axon, or longitudinally along it. But this is the place to start, at the square-micron level.

To detect helically wound channels, one might try to sense a tiny electronic phase shift in response to a substantial change in the magnitude of the stimulus, but it would probably wash out. The existence of multiple channels in whatever configuration will be difficult to detect at this scale, although it should help that they are probably periodic structures.

Zero

It would help the multichannel model to have a zero setpoint, and a full number line range from positive 300 through zero and down to negative 300. If you split the clock like this, you can communicate finely resolved degrees of stimulation (or motor instructions) that have a direction. This makes it possible to traffic in signed concepts like forward and backward, up and down, more than zero and less than zero.

It is also possible within the model to bias the zero position for a neuron that needs, for its typical stimulus, a larger positive than negative range, or visa versa.

At the synapse, an excitatory potential is measurable electrically, but the actual messages – the finely resolved increments of excitation – are not detected.

On the axon the message is the channel number. Electrically the message is not detectable, at least not yet, but detection seems possible, promising. But at the synapse, the message is likely to be embodied as a biochemical messenger. It is difficult to detect a biochemical message with an electrically sensitive instrument. And we are looking for a subtler message – probably many of them – than our standard menu of neurotransmitters can provide.

In other words, the model calls for the successful transmission, across the synapse, of a channel number. This could be done electrically by re-creating or representing the potential originally perceived at the sensory end of the nerve. It could also be accomplished with a chemical messenger packaged into the synaptic vesicle along with the neurotransmitter. Maybe a peptide unique to each channel. The channels are physically distinct from one another, so one might look for specific cell surface receptors for these peptides (or whatevers) on the receiving nerve membrane. Finally, there could be some anatomical structure, or useful proximity, that helps conserve the channels’ identity as the message traverses the synapse. The simplest way to model it would be to allocate one dedicated synapse to each of 300 channels.

The traveling array of pores

If you put two pulls on an ordinary zipper, you can create an open pore that travels. It is easy to mimic this kind of mechanism or reproduce its effects by linking unit Na+ channels.

The image of a zipper with two pulls, one closely chasing the other, applies nicely. Suppose unit sodium channels are linked to produce a longitudinal channel the length of the axon. The unit sodium channels are normally closed. Each has a discrete pore that is opened by a voltage sensor to enable Na+ ions to tunnel through the neuron’s cell membrane into the cell. Each tunnel narrows to about half a nanometer in diameter. Only sodium ions can pass this constriction.

The successive opening of the pores along the line of unit channels is trailed in time by the automatic inactivation, i.e. blocking, of these pores. This creates in effect a traveling linear array of open pores that admits sodium ions as it progresses along the axon.

Just ahead of the leading pore, a new leading pore pops open. At the end of the line of open pores, the trailing pore is blocked and in effect, snaps shut. The pores themselves are stationary, but the array of open pores progresses in single file down the axon toward a synapse.

One also could link in, with a lag effect the potassium channels.

The firing of a single selected numbered channel may not be energetic enough to produce on the screen of a scope the familiar action potential we expect to see. To solve this in the model one could pepper the membrane with unlinked unit channels. This would produce a more robust action potential.

Multichannel communication would be unaffected by unlinked sodium ports opening nearby because only the linked channels lead to synapses. The isolated, unlinked Na+ channels admit additional sodium ions and produce a textbook wave of depolarization that accompanies and helps power the real signal — but leads nowhere. In other words isolated unit channels could provide an enhanced power supply. They would thus have a supporting role to play in conveying a signal — a channel number — to the next neuron.

Testable hypothesis

The addition of unlinked unit Na+ channels creates an effect that could be used, experimentally, to seek evidence that the multichannel neuron may exist in the real world. Axons often branch into multiple tendrils called telodendrions. These fan out to other neurons and terminate in synapses.

The unlinked unit sodium channels should sustain an action potential launched from the hillock all the way out to the synapses at the ends of each of the axon’s branches.

But then what?

The multichannel model stipulates that only signals in passage along linked and numbered channels can traverse the synaptic cleft to another neuron. This suggests that although every telodendrion will sustain an action potential to its own end, only a few — let’s say one — could actually fire the neuron beyond its terminal and synapse.

It should be easy to change which telodendrion is capable of firing the neuron at its terminal. Stimulus intensity is the independent variable. A sharp increase in stimulus intensity would push the channel number higher. This should result in the firing of a different output neuron. At each stimulus intensity level tested, a different and specific output firing neuron should be detectable, and this result should be reproducible.

The formal premise is that a sensory nerve’s axon contains multiple transmission channels and that at least some of these channels are embodied in telodendrions and (a logical AND) there exists a mechanism ahead of the cell body which selects which of the multiple channels will carry a signal down the axon and onward to another neuron via an outbound synapse. The channel selection is based upon the intensity of a sensory input.

In explaining the experiment, it is helpful to make the payoff the firing of a following neuron. A better experiment, however, would simply look for evidence that a signal had successfully traversed the synaptic cleft. So a better set-up might be to monitor the excitatory post synaptic currents at each synapse touched by a telodendrion. This would make it possible to declare that a single channel’s signal had crossed the cleft — and that no other telodendrion’s output signal had made the leap.

The hypothesis would be false if all of the telodendrions’s signals were detectable beyond their respective synaptic clefts.

Incidentally, the idea of numbered synapses is not new. The idea there might be some sort of detectable ordering or sequencing of synapses on the dendrites is attributed to Wilfrid Rall, who suggested it in 1964 in support of a wholly different and unrelated model of the nervous system.

The problem of inhibition

Inhibition is a thoroughly studied effect, but in the multichannel model it may have an undetected aspect. In the multichannel model, inhibition essentially turns off the nerve — stops communication altogether. As in the traditional analysis of inhibition, hyperpolarization at the input of the neuron requires a stronger stimulus to overcome. Thus, an inhibitory potential raises the theshold level of the stimulus that must be applied for the neuron to resume firing.

More complicated things can happen with the model, however, because the multichannel neuron can be inhibited in a very direct and immediate way by freezing the commutator in one place — in effect, locking the brake.

What purpose is served by this different mode or understanding of inhibition? Why turn off a nerve, or lots of nerves? What could be its operational purpose in the brain, for example?

In an individual neuron that has been overdriven, and for some reason cannot successfully adapt (rescale), it might be useful to shut down this neuron to end the oscillation. In this model, continuous firing is a pure waste of energy. A momentary stop or hiatus might also be inherent in the normal process of adaptation.

Stopping certain neurons or systems of neurons from communicating can be a control system that helps focus attention, or improve a signal to noise ratio in certain areas. If inhibition is highly coordinated, it could provide the basis of a scanning (spotlight of attention) system or a multiplexer.

The failure or overactivity of a novel, unsuspected biochemical mechanism of nerve inhibition could be significant in understanding processes such as epilepsy, cortical depression or narcolepsy. I suppose one could even project the problem into large mysteries like intelligence or sleep.

To keep this on the ground, let’s note again that what we have here is a model neuron. This model can be turned off by freezing the motion of the channel selector. This Off-switch may operate when the nerve is hyperpolarized, as in the traditional, textbook sense of inhibition. But it might also switch off the neuron, or populations of neurons, for important reasons at other times as well. The problem leads to questions of cause and effect, since the cessation of firing can produce hyperpolarization. It appears from the model that this novel form of inhibition, by halting the commutator, could be made to act instantly.

A high frequency stream of action potentials impacting the axon’s presynaptic terminal can induce persistent biochemical changes on the far side of the synaptic cleft, including a proliferation of neurotransmitter receptors. New, additional receptors induced by an original stream of impulses thus makes the post synaptic terminal more responsive, electrically, to subsequent streams of incoming action potentials. These changes can be long lasting.

Biological memory can be defined as a persisting biochemical change in response to a change in the world. An increase in synaptic strength has for many decades been regarded as the basis of memory.

Historically, improved synaptic strength in response to sensory experience has been used by theorists to create nervous systems within the nervous system — grooved-in pathways or networks or, roughly from the 1930s into the 1970s, “reverberating circuits.”

More recently it has been used to create neural networks on computers, able to learn, based upon distributed weightings at nodes analogous to synapses.

Persisting synaptic strength as a marker and store of memory is a keystone concept in contemporary neuroscience. Two major experimental systems, in the invertebrate aplysia (sea slug) and in the vertebrate hippocampus have been used to test and detail the mechanisms and biochemical pathways of persistent enhancement of synaptic strength in response to worldly experience. In the literature you will sometimes find memory and increased synaptic strength used as though they were synonyms.

However, in 2015, in the MIT lab of Nobel laureate Susumu Tonegawa, it was demonstrated by Tomás J. Ryan et al using optogenetic manipulation that a memory can be stored in a mouse’s brain without the expected alterations of synaptic strengths. Alterations of synaptic strength can be suppressed completely by protein synthesis inhibitors. The experimenters trained a mouse whose ability to alter synaptic strength had been shut off in this way.

Demonstrably, no synaptic changes occurred in the course of training. Yet the mouse somehow stored the memory of its training. The memory could not be retrieved in the conventional way — it had to be coaxed out of storage using light stimulation of targeted memory neurons. But the memory existed. It had been stored.

The Ryan paper presented the first serious experimental challenge in many decades to the widely accepted concept of synaptic memory. A follow up paper in PNAS in 2017 clarified and amplified on the notion that memory is not, after all, stored by improving synaptic strength. Here is a news article from MIT that includes some interesting commentary by the investigators.

The hypothetical nervous system constructed with multichannel neurons does not depend upon synaptic strength as a memory medium. In a multichannel neuron, which is the hypothesis we are discussing here, the content of memory is a channel number, and it exists and persists from the instant of sensory detection. An action potential coursing down an axon conveys the memory of a channel number from hillock to synapse.

For us, the problem at the synapse is not storage. The problem at the synapse is how to transmit an incoming analog value, a channel number – intact across the cleft and beyond it to the axon hillock. The synapse is critical in this model because a synapse does not simply connect neurons. The synapse marks the output of an individually numbered transmission channel.

Where can we go with this?

One might reasonably ask why, in a system with up to 100 billion neurons at its disposal — why add 300 channels of fresh capacity to each single neuron? If you need 300 channels for whatever task, why not just recruit 300 one-channel neurons?

The overarching argument is speed-of-thought. By increasing the channel capacity of the nervous system by just two or three orders of magnitude, from 1011 up to 1014 for example — we can eliminate encoding and decoding and create a dazzlingly fast brain.

But there is an additional argument for a multichannel neuron. A specialized sensory cell — a rod or cone for example — is badly served by a one-channel output line. Very badly served.

What would it mean to our understanding of sensory cells like the retinal rods or cones, or the hair cells of the organ of Corti – this fresh assumption that there exist 100 or 200 or 500 distinct channels of upstream transmission capacity in a single axon?

We notice, for example, that there are hundreds of light sensitive discs stacked into each individual rod cell of the retina. Lots of sensitive hairs on a single hair cell in the ear. Lots of discs center-tuned to a specific color wavelength stacked into a cone cell.

Yet these multiple repetitive sensory structures, begging for calibration, begging to tell us something sophisticated and finely incremented and highly detailed about space or frequency or intensity, perhaps even phase — are supposedly served by a single preposterous drainpipe of an output channel.

As presently understood, a cone cell is just a one-channel light meter. It reports only on its perception of the intensity of impinging light — and nothing more. Even if the cell had something more to tell us (that is, to tell the brain) it could not get its messages through in realtime or near realtime.

Information from a photoreceptor must ultimately be funneled into a retinal ganglion, an output neuron with the standard, simplistic all-or-none axon. All information about the retinal image that can be made available to the brain must be transmitted along the single channel, all-or-none axons of the retinal ganglion cells. There are in the retina of one eye about 125 million photoreceptors. From all these inputs, the output cable of axons from the retinal ganglion cells is just 1.2 million lines, essentially a 100-fold reduction. In this sense the optic nerve is a horrific theoretical bottleneck. For multichannel neurons, the bottleneck does not exist. The optic nerve could have a half-billion channels.

We know a cone cell of the retina produces an output potential which varies as a function of light intensity. Maybe it does much more. It might even produce and transmit, given a multichannel neuron, information about light intensity sensed at each disk within the cone cell. Such a cone could return to the brain a precis on intensity patterns (for example, standing wave interference patterns) at various planes along the cone cells’ z-axes in the fovea.

Other ways to apply this ability to detect intensity peaks and patterns along the z-axis of each photoreceptor would be in detecting chromatic aberration, or perhaps in remarking spatial phase.

You can limn suppositions like these about pressure sensors, acoustic sensors, olfactory sensors. In brief, there could be much more information emerging from sensory organs than we ever imagined. We should be more ambitions for these sensors, given a multichannel neuron.

The Good Address

Computer circuits depend absolutely on memory storage addresses. Are there addresses in the nervous system for the sources and sinks of information? It is problematical because nerves branch.

Visualize a nerve trunk served by 7 or 8 dendrites fanned across some tissue, the skin of the fingers, let’s say — each dendrite ending at a distinct point. An impulse glides up the central trunk. The brain must ask — Where did this impulse come from? Which finger, which branch, which dendrite was the original source?

Once the impulse reaches the central trunk, it would seem the source’s address is lost.In a corduroy neuron, however, the multiple channels can be used to conserve the identity of the source. In the model, a channel’s meaning is arbitrary. It can mean 25 mV, -25 mV, or +15 degrees or –15 degrees, or it can mean, “left little finger” – an address.

The brain needs a dual signal: of an address for the originating tissue, associated with a number representing an analog intensity level. It would be very computeresque. Probably evolution would have combined the address+information channels in a single neuron, by segmenting the available channels (say 300 of them) into five sets of 60 analog channels – each set of analog-increment channels corresponding to an originating dendritic branch and stimulus sourcepoint.

The address channels probably came first, and the (additional) information channels were probably added later, by duplication. Duplication is a favored process for effecting evolutionary change.

Where the idea came from.

This multichannel neuron model is one answer to the question, how could a single impulse convey information to the brain – inform a racing bat it’s time to swerve, just in time. Other models may suggest themselves, but I rather like this one.

It popped up when I was wondering how you might design an instrument to determine whether or not a nerve impulse was moving straight up the pole of the axon, or if it were, simultaneously, spinning around it, or wobbling.

The idea was to discover what degrees of freedom were still available to the “all or none” nerve impulse. We know it translates. This leaves vibration and rotation.

I have not solved the instrument but when I started wondering why the impulse might want to oscillate or spin, and how it might be compelled to do so by some underlying membrane structure, it seemed a window suddenly cracked open on the problem created for us by Hermann von Helmholtz 175 years ago. We’ll see.